This article is available as a PDF on the Internet Archive here.

Pagans Hill in Somerset around the year 262 CE an octagonal temple was constructed alongside a well and ancillary buildings which supported visiting pilgrims, staff, and the construction of the temple itself. The site is of importance for the ways in which it shows us changing religious practices and beliefs over a tumultuous time period spanning the final centuries of the Roman west to the emergence of Early Medieval society. With its initial construction during the Gallic empire, and significant physical redevelopments spanning centuries, these changes in behaviour and belief are built into the stones of the temple itself.

This temple was built over an earlier round barrow that seems to have drawn the attention of locals since at least the 2nd CE, and the Iron Age inhabitants before them. By the end of the 3rd CE the temple experienced a period of decline before being renovated with new features and new rites during the middle of the 4th CE. During this period pilgrims visiting the temple would have entered from the east, departing from the nearby Roman road. They would have climbed Pagans Hill and been greeted by a colonnaded veranda where perhaps they would have been met by temple staff or have been able to rest sheltered from the sun and rain and prepare themselves before entering the temenos. Still, perhaps the space may have been intended to provide room for merchants to sell supplies and offerings to the pilgrims, though there is no archaeological evidence for this scenario.

Those same pilgrims would have then passed through a central gateway into the courtyard where they would have first seen the temple in its full grandeur. They would have seen it painted in reds and whites, with decorative motifs including medallions and borders in a wider range of colours; yellow, orange, green, blue, and pink. The ambulatory tower of the temple would have reached just over five metres - its position at the peak of the hill would have made it the highest building in the area. If the roof ridges were decorated with finials alongside the bright colours of the walls, the temple would have been quite a sight.

Entering the temple into a reception space they would have been greeted by three doorways, the left and right leading into an ambulatory wrapping around a cella made of eight stone piers with archways in between. If the doorway directly in front was open, visitors would have been greeted by the idol of the god in the form of a young hunter wearing a Phrygian cap and flanked by his loyal hound. It has been suggested that this was the god Apollo Cunomaglus, better known from the nearby Nettleton Scrub temple.

The temple itself would survive the end of Roman Britain, providing a place for early medieval elites to feast and display their wealth. It would continue to stand through the medieval era, ultimately falling to Victorian stone robbers.

The Landscape

If travelling to Pagans Hill, the nearest easy spot to park is alongside the private road leading up to a car dealership just off of Scot Lane. But this is only a small road, suitable for one or two vehicles. The roads heading towards the site are all narrow and have no pavements, so if parking further away you will have to walk along the road with care.

The field is accessible via a public footpath from Scot Lane at the south-east end of the field. The public footpath begins at a cattle-gate which is often left open, but otherwise there is a kissing-gate on its right hand side that requires a small step up. The field appears to be regularly used for cattle, and so in winter the path can be very uneven and churned up from the cattle or potentially blocked by the herd.

The temple site itself is not on the footpath, but is to the west of it by about 100 metres and up the slope of the hill. The spot of the temple itself is identifiable by a gentle slope, and its outline as well as the surrounding buildings are clearly visible on LiDAR.

The site is situated on the western side of the Chew Valley - just north of Chew Stoke - and lies on top of a small promontory that rises 110 metres above sea level. It overlooks the valley eastwards with the Mendip hills to the south, the ridge of Dundry bounding the north, and hills rising in the east towards Bath, providing an all-encompassing view of the valley. The valley follows the River Chew, which feeds into the Avon and an artificial lake that was built in the fifties to provide water for Bristol and the surrounding areas.

The valley immediately to the south-east appears to have been dominated by small rural communities focused on agriculture and iron production. These are in the immediate vicinity of a villa, as well as a palisaded cemetery enclosure at the western outskirts. These sites are 3.5 to 4 kilometres away from the temple site, and all but one now lie under Chew Valley Lake.

Just to the east of the lake, two minor Roman roads crossed. One (Margary 540) heading north-east towards Keynsham and south-east through the lake where it would join the principal road heading towards the Fosse way, and the other (Margary 546) north-west to Bristol and bending south-east towards the Fosse way near Radstock.¹ The name of the site is remarkable but a coincidence, and seems to indicate no religious association. It is considered to be derived from the ’Payne’ family who were local landowners known from the late 13th CE.

The name originally applied only to the nearby farm, the hill appearing in tithe maps as the prosaic ’Great Green Hill’.² Various interpretations have been put forward for the etymology of ’Chew’ valley, including connections to a Norman term for a river, an Old English term for fish, and even a British derivation interpreted as ’the river of the chickens’. But all seem to agree that ’Chew’ is not to be derived from the Old English theonym ’Tiw’, as interesting as that would be.³

Excavation History

The first mention of any Roman building at Pagans Hill is in a diary entry of Rev. John Skinner from 1830, where he observes a stone-robbing event by the owner of the land, a Mr. Gray. Skinner believed that the building was a beacon tower, and reported a freestone finial which he provided a sketch for. The finial is very similar to one from the Nettleton site, which Wedlake described as ’being in the form of a miniature temple’.⁴ According to Skinner the finial was taken to the garden of Mr. Gray, and it cannot now be found.

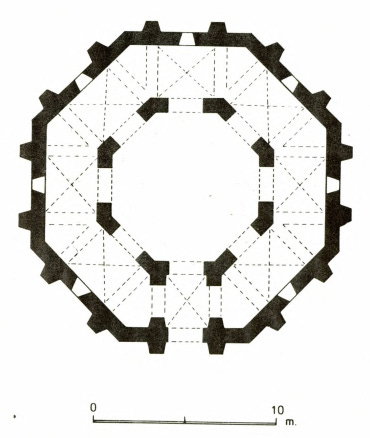

First archaeologically excavated between 1949 and 1953 by Rahtz and Harris, the initial excavations revealed an easterly facing octagonal building that was immediately interpreted as a temple in their 1951 publication. Their interpretation was based solely on the plan of the site, comparing it most closely to the Weycock Hill site and relying on its interpretation as a temple by that site’s excavator, saying that ’there is no reason to dissent from this view’.⁵ They also pointed out the building’s similarity to early Christian baptisteries, especially the early 5th CE Lateran Baptistery at Rome (see fig. 4) with its double octagonal form - which seems to have greatly influenced Rahtz’s reconstruction - and smaller examples at Aix and Riez.⁶

In the pair’s later excavations they would uncover the well a little over 5 metres behind the temple to the west, and a range of ancillary buildings to the east, north east, and north of the temple. The well produced some of the most important finds from the site, including a statue of a dog - thought to be part of a cult statue - and a rare Early Medieval glass vase. The eastern building - which overlay an iron age ditch way - was split in two with two long parallel rooms either side, and a gate through the middle in line with the temple’s entrance. It might have been some kind of reception area or sheltered space for worshippers,⁷ but so few finds came from this building that it is difficult to interpret. The north-eastern building appeared to serve a domestic purpose, and being smaller than the eastern building is thought to be a living space for temple staff or pilgrims,⁸ and the northern-most building shows evidence for industrial activity, being interpreted as a workshop to support the construction of the temple.⁹

Further excavations would be taken out in 1986 in an attempt to clarify ambiguous details from the earlier excavations, and would reveal a refuse pit to the south of the temple¹⁰ and a wall trench to the south-east which has tentatively been interpreted as part of a temenos boundary.¹⁰ The refuse pit produced the largest amount of animal bones from anywhere on the site and are the subject of a study providing us with an understanding of what kind of animals were present and how many were slaughtered on the site.¹¹

The Temple building

The temple was fifty-six feet in diameter, with a nine foot wide ambulatory, surrounding another inner octagonal cella twenty-six feet in diameter, the entrance to the ambulatory appeared to have a metalled surface forming a ramp leading up to it.¹²

The cella had an east facing entrance aligned with the ambulatories entrance (see fig. 5). Beneath the temple a layer of pre-historic material was discovered that included sherd fragments of coarse pottery, flints, and an oval depression.¹³ The oval depression was packed with clay and stone, among which a small amount of charcoal and bone was found.¹³ Rahtz provides three possibilities for the depression; a foundation deposit for the temple, a burial ’perhaps with a token or even an embryo interment’, or a round barrow which had been levelled by the construction of the temple.¹³ Grinsell favours the round barrow solution,¹⁴ and this is supported by the fact that it is not un-common to find barrows associated with temples in Roman Britain such as Brean Down,¹⁵ Bourton Grounds,¹⁶ and Haddenham.¹⁷

The building had solid foundations of dry built and un-coarsed rubble - three to four foot deep in places - supporting walls nearly 4 ft thick, with two buttresses on each external angle.¹ The internal side of the entrance to the ambulatory is marked by two internal projections opposite to the external buttresses (fig. 5). These are matched by two slightly smaller projections from the external cella wall, showing that the entrance to that section was also east facing (fig. 5). The roof was tilled with pentagonal shaped tiles.¹⁹ Rhatz uncovered some limited evidence for windows in the form of a monumental window-head, crushed alongside other pieces of rubble either side of the entrance ramp. However no glass that could have been part of the windows was found during any excavations.¹⁸

Lewis has suggested vertical dimensions proportional to its overall diameter, so that the ambulatory could rise as high as 5.17 metres (30% of the diameter) and the cella to 10.33 metres (60% of the diameter).²⁰ Later authors have followed this and consider it a reasonable estimate, even if we cannot know for certain without supporting archaeological evidence.

The internal floors were made of clay and stone chippings, and had first been levelled against the slope of the hill, before large irregular flagstones were placed over the top and lightly mortared in place. The floor level of the cella was raised 1 - 2 feet above the level of the ambulatory. No flag stones were found in the cella, but this is more than likely due to stone robbing and Rahtz considered it probable that it was paved in the same way as the ambulatory.²¹

Fragments of wall plaster associated with the external wall were found both outside and inside the ambulatory.²² Rhatz reports that due to robbing we cannot form a general idea about the distribution of colours and designs, but the fragments show that the temple was painted mainly in red and white with stripes and panels in yellow-orange, greenish-grey, green, pale blue, and pink.²³ We also see fragments showing large ’medallions’, as well as red ’splashes’ on a pink background found only around the outer entrance.²³

The lack of plaster fragments around the internal cella foundations has led to some debate about its appearance. For Rahtz, the lack of plaster fragments is evidence that there were no solid walls in between the ambulatory and the cella. He suggests this was an ’open’ cella with perhaps a colonnade of columns, and vaulting based on the presence of tufa on the site - a relatively light rock suited for the purpose.²⁴ This is despite the lack of any pillar bases being found on the site, except one from the well which could have been from one of the ancillary buildings rather than the temple.

Rodwell dismisses Rahtz’ theory and re-imagines the internal architecture.²⁵ He considers the internal projections either side of the ambulatory and cella entrances to be evidence for internal lateral arches, and that at least here they could not have been supported by Rodwell’s ’slender’ columns saying:

”These significant features appear to have been overlooked, but they constitute prima facie evidence for a pair of lateral arches in the ambulatory. Thus the cella foundation on this side at least cannot have supported columns: the responds must have been attached to something more solid.”²⁶

He believes that each of the other six external angles of the cella would have also had these solid ’piers’ instead of columns, on the grounds that it would have been ’archaeologically uncomfortable’ otherwise.²⁶ This dissents not only from Rhatz, but also Lewis who believes piers would have been plastered,²⁷ Rodwell dismisses this as an unnecessary assumption.²⁸ He goes on to suggest that this entrance area defined between the arches and the entrances would have been closed by doors or gates, comparing it to similar reception areas at other temples, including Caerwent, Brean Down, and Lamyatt Beacon.²⁹

He also makes the point that the buttresses on the external wall were not positioned correctly to prevent settlement cracking or support the weight of the ambulatory roof.²⁶ He suggests that these would have been better suited to support vaulting, imagining sixteen vaulting ribs springing in pairs from splayed corbels at each of the cella angles and terminating in two single corbels either side of the ambulatory internal angles (fig. 7).

The intermediary spaces between these pairs of ribs could be filled with cross vaulting, this for Rodwell would achieve an architectural unity and produce a labyrinth like affect:

”Thus the ambulatory and the cella would achieve an architectural unity, with no awkward junctions, the recessed porch would not obtrude itself on the interior, and to the observer from within the cella the temple would have appeared to have a labyrinth of side chambers”.³⁰

Rodwell also imagines that in between these angles the cella would have been accessible through round-head arches, potentially protected by gates or grills.³⁰ This last point seems more based on a personal concern for architectural aesthetics and security, but would explain the lack of wall plaster in this part of the temple.

Between the entrance to the ambulatory and the entrance to the cella, Rahtz described a ’foundation’, 1.2m by 0.45m, embedded into the floor layer and projecting slightly above the flagstone paving.³¹ He tentatively interpreted this as the remains of an altar, comparing it to a feature found at a similar position from the Romano- Gaulish temple in Chassenon.³² But Koethe describes this feature at Chassenon as a basin, possibly for water or even blood, or perhaps as a void for an altar base.³³ Aupert also considers it a basin which may have been filled with water for ablutions and purification,³⁴ so this is not an apt comparison with the feature at Pagans Hill which projects above the ground level. Traditionally we would expect an altar to be present immediately opposite the ambulatory entrance in the courtyard, but no altar has been identified in this space. This is not so surprising as very little of the space in-between buildings has yet been excavated, which is where we might expect much of the ritual action to occur.

At the centre of the cella, Rahtz uncovered an ’L’ shaped foundation made of large stones. He conjectured that when complete this foundation would have been symmetrical, forming a kind of ’C’ shape.²¹ Rahtz suggests it may have been associated with cult-objects and compares it to similar structures at temples in Herapel and Saint-Révérien, where Koethe suggested that they were used for supporting a cult image or a group of statues.³⁵ When referencing this structure Rodwell uses the term exedra,³⁶ a kind of large semi-circular bench, and Boon uses the term reredos,³⁷ a kind of screen for displaying religious imagery, usually behind the altar of a church, so there is some confusion on how exactly to describe this feature.

Beneath this foundation in the cella a coin of Gratian - dated from 367 CE - was found.²¹ This is noteworthy as the only stratified coin found in the temple building, most of the coins from the temple were found evenly scattered across the site, the exception being a group of 25 coins - almost a third of the total from the temple - found just to the south of the ramp and all dating from the 4th CE.²² These coins to the south of the entrance ramp have been interpreted as offerings,³⁸ which must have been placed to the left by pilgrims as they enter the temple, or to the right as they exit.

This single stratified coin of Gratian has been used in interpretations as a terminus post quem for a possible revival in activity at the temple after a period of decline.³⁹ This decline is interpreted from a paucity of finds in the well between layers dating to the late 3rd CE and early 4th CE.³⁹ Shortly following on from a phase in which building material from the temple - potentially being damaged - was dumped into the well.⁴⁰

The Well

This well was man-made and dug to a depth of 8.2 metres.⁴¹ The bulk of stratified finds at the site were recovered from this including the building material from the temple, pottery, an early medieval glass jar and iron pail, and the statue of a dog which is thought to be a part of the temple’s cult statue.³⁷

Rahtz split the well into seven layers from A - G divided by the make-up of material at different depths. G is the bottom of the well, marking its initial construction, and A the top where rubble has clogged the mouth of the well. Layers D through G are the only Roman layers, and are thus contemporary with the temple’s construction and primary use. Interspersed amongst all of these layers is rubble, fragments of buckets, and pottery representing jugs, jars, and mugs.⁴²

The pottery has been interpreted, in part, as accidental loss of vessels which would have been used for retrieving and carrying water from the well.⁴³ This is probably the case for the bucket fragments and any complete set of sherds. Where only loose unrelated sherds were found these have been considered litter which accidentally made their way into the well. Rhatz assumes this because of a lack of bone, and so it is probably not wholesale dumping of waste.⁴³ This seems to be confirmed by the refuse pit to the south of the temple, which did have a large quantity of bone and generally a very different make up of material compared to the well.¹⁷ The pottery was more numerous at layer E, which had at least 30 - 40 pots, twelve of which have been restored. The quantity tapers off above and below this with layers D and F having only a few sherds of pottery.⁴⁴

The rubble in most of the layers seems to have been predominantly loose freestone and some roof tiles, which may have ended up in the well by accident or to clean up the area.⁴⁵ It could have come from structures around the well, as at layer D un-burnt oak wood was found which Rahtz suggests came from a collapsed super- structure over the well.⁴³

Layer D also produced Constantinian coins, one of which is dated 333-35 CE - much later than those of layers E and F, after a period of diminished activity.⁴⁶ Layers E and F contained coins which can instead be dated specifically to 260-70 CE, very early in the site’s history.⁴⁶ At layer F the makeup of the rubble also changes - at this point it appears to be mostly building materials; roof tiles, roof-coping, mortar, a column base, and freestone.⁴⁰ This building material was analysed and found to be more similar to the material recovered from the temple itself than any other building.⁴⁷ Above layer D we begin to see early medieval material, so this represents the end of the Roman period on our site and probably a further pause in activity, at least related to the well.⁴⁶

Rhatz’s interpretation of these layers is that the large amount of building material at layer F came from the temple after either significant alteration or damage very soon after the temples construction.⁴⁰ The presence of pottery and bucket fragments here and at layer E show that the well increased in use immediately after this event. There then appears to be a pause in activity until the early or mid 4th CE, after which activity at the well seems brief and less intense than it had been. The revival of the temple is dated to around 367 CE.²¹ While this last layer could be associated with the start of the revival it is clear the well goes out of use around this time, or at least plays a very different role at this phase of the temple’s life.

The statue of the dog from layer B is probably the most significant piece of evidence for our understanding of the temple to come out of the well. Now 63 cm in height and badly damaged, it is missing its head entirely and has a hole passing laterally through its chest.⁴⁸ Originally thought to be a 16th CE garden ornament, Boon later showed that it was a late 3rd CE Roman figure, and that it was originally attached to and supported a larger human figure.³⁷ He compares it to the figure from Southwark known as the ’hunter god’, which depicts a male youth with a quiver at his back, a deer on his left, and a hound at his right sitting and looking up towards the figure in a nearly identical posture as the Pagans Hill figure.⁴⁹

A stone head picked up near Pagans Hill depicts a figure wearing a phrygian cap that Boon suggests was a part of the same statuary as the hound. This similarity to the Southwark figure led him to suggest that the figure from Pagans Hill was the same as, or else very similar to the Southwark figure.⁵⁰ Unfortunately the stone head is now lost, its last known whereabouts was with a family in 1914 before it entered the antiquities trade. Boon goes further and identifies this figure with the god Apollo Cunomaglos, who was worshipped at the nearby octagonal Nettleton temple.

Another important find from the well was an Early Medieval blue glass vase which was dated to between the 7th and 8th CE. Evison has argued that it is of a type that is usually associated with the royal household of the kingdom of Kent.⁵¹ The vase probably began its life as a diplomatic gift, whether the owner at Pagans Hill was the original recipient or further down in a chain of gift giving we cannot say. Its presence in the well, alongside an iron pail, flecks of charcoal, ox and sheep bone tells us that there was a presence at the site at that time. We know that a significant amount of the temple was still standing because some of the roof fragments discovered in excavations had fallen on 12th CE pottery, and so the temple could still provide shelter in the Early Medieval period.³⁹

The Refuse Pit & Animal Remains

During the 1986 excavations the refuse pit was identified to the south of the temple.¹⁰ It was 20 metres away from the temple, near the modern tree line, and appears to have been part man-made and part formed from the natural slope of the hill. In the pit were found sherds, building material, flints, shale, two undated Roman coins, and around 200 animal bone fragments. No carbon dating has taken place, so the whole assemblage is considered ’Late Roman’⁵² as it is assumed the pit must have been filled during the temple’s construction or its lifetime.

The animal bone from this refuse pit was analysed by Gilchrist as part of their 1989 study.¹¹ Quantification of the bones showed the species present as cattle (80.1%, minimum individuals 3), sheep (11.8%, minimum individuals 2), pig (7.4%, minimum individuals 2), and goat (0.6%, minimum individuals 1), as well as other unidentifiable species (20.9%).⁵³ Analysis of these bone fragments provided approximate ageing for the sheep and pig (sample size 1 in both cases) as ’sub-adult’, and the cattle as 2 ’adults’ and 1 ’sub-adult’. The samples were insufficient to provide any data about the sex of the animals. Due to the identification of ’sub-adult’ animals - of the minimum eight individuals, only two cattle were explicitly identified as ‘adult’ - leaving three to five ‘sub-adults’ minimum. This suggests a seasonality to the slaughter, as young adult animals would only be available at certain times of year. We might also suggest that these animals were not slaughtered purely out of a utilitarian nutritional concern, adult animals would have provided more food and probably at a lower cost.

The assemblage showed evidence of butchery as bones had chop marks, had been cleaved in two, or long-bones which had been sawed open to access the marrow.⁵² Gilchrist discusses this as evidence for food preparation and consumption on the site, especially as the bones represent the meat-yielding elements of the animal such as ribs, long-bones, and fore-leg joints. Burnt bones were also present in the assemblage⁵³ so it is likely cooking as well as butchery was taking place nearby.

The site produced unusually low numbers of bone fragments. Here we have around 200 fragments of bone, whereas Nettleton produced 555, Bath 8,000, and Uley 232,322.⁵⁴ The vast bulk of these bones came from the refuse pit, however it produced very few skull or metapodial fragments,⁵² suggesting that after butchery certain elements of the carcass were being separated and treated differently. At other sites we see non-meat yielding elements being separated and displayed, for instance at Uley the horns of sacrificed goats are thought to have been displayed as trophies.⁵⁵ Without these missing remains we are precluded from forming a full theory as to how these animals were slaughtered and the way their remains were used.

Whilst a reasonable assumption would be that the animals were butchered as part of the cult activities at the temple, Gilchrist considered these animal bones to be wholly ’domestic’ by-products of kitchen and table food waste.⁵³ They note the exclusion of non-livestock animals such as cockerel, dog, or snake which they would expect in a temple and that ’the activities implied by the bone are not specifically associated with ritual deposits’. However in a 2005 study of animal remains found in temples in Roman-Britain, King showed that finds from temples do not typically diverge from the species in the diet of the general population - namely ox, sheep/goat, and pig - even if the proportions of each and how they are treated can vary.⁵⁶ Even agreeing with Gilchrist that these were not instances of ritual deposit, given the religious context and the conformity with a regular late-roman diet these remains are probably best understood as resulting from alimentary sacrifice rather than simply ’domestic’ by-product.

The Outer Buildings

To the east of the temple was a long structure stretching north to south made up of four rooms around 18.2 metres long each - two on the western side and two on the eastern side - with a gateway around 3 metres wide splitting the building in two.⁵⁷ The gateway is aligned with the entrance of the temple and was probably the main entrance to the complex, worshippers having travelled west from the nearby Roman road and climbing the hill to be greeted by a view through gateway and possibly into the temple on the other side.

Underlying this building just to the north of the Roman gateway is an Iron Age ditch, 2.1 - 2.5 metres wide and flat bottomed. It curves to the north slightly - and it cannot be traced any further - but leads west to east towards the location of the temple and the round barrow beneath. It’s thought that this may represent a path-way created in the Iron Age to access the hill-top.⁵⁸

The eastern building has proven difficult to interpret as very few finds are associated with it. No plaster was found, and domestic debris or pottery is almost entirely absent. Because of this Rahtz believes that the eastern side of the building was a veranda but otherwise suggests that the building was rarely used.⁵⁹ In later publications it is referred to as an ‘abaton’,⁶⁰ a kind of enclosure usually only accessible to temple staff - and particularly associated with the temple of Asclepius - but this interpretation is not elaborated on by the authors.

Rodwell pointed out in 1980 that the eastern building, the temple, and the well are all laid out on the plan of an isosceles triangle, with the sides being drawn from tapering sides of the eastern building.³⁶ With the gateway, the temple, and the well all aligned along its central axis, and the distance between the gateway and the temple being equal to the distance between the temple and the well. This has been assumed as evidence that these features must all be contemporary, being planned together.

To the north of the temple was another building made up of six rooms, completely robbed out of any floor layers or foundations so that we only know its form from the wall-trenches left behind.⁶¹ It produced almost as little material as the eastern building except for a large amount of iron from metalworking in the south-western corner. It is aligned with the north-eastern building, and may have been contemporary to it, but due to the severe robbing any stratification from the space between these buildings has been obliterated. The only dating evidence from this building places it in the late 3rd CE, and so Rahtz suggests that it was an early workshop built to support the construction of the temple before being destroyed.⁶¹ The north-easterly building may have been attached or simply re-used the foundations of the now lost eastern end of the building.

The last building on the site is the north-eastern structure. It is traditionally split up into nine rooms, though some of these seem to have been sectioned off portions of a courtyard. This building provided the greatest amount of material. Appearing to have been largely domestic, this included coins, pottery, small finds including a trowel and a chisel, and plaster - the only location to produce any other than the temple itself.⁶² Based on the dating evidence the building appears to have been roughly contemporary with the rest of the site, producing two 3rd CE coins but mostly early to mid 4th CE. A single coin of Valentinian I was the only legible 4th CE coin found - and that was un-stratified. Based on this Rahtz suggested that the building did not stay in use long past the middle of the 4th CE.²² Notably, a potential burn layer was identified in two of the rooms, which may be the cause of the buildings decline.⁶³ The terminus post quem for the revival of the temple is 367 CE (provided by a single stratified coin of Gratian), so it may be the case that the building was damaged by a fire not long before this revival, but was not itself reconstructed with the temple.

In the angle between the north-eastern building and the northern building was a metalled surface which produced no occupation material, over this was a layer of clay which Rhatz believes derived from the digging of the wall trenches for the north eastern building.⁹ Underneath this layer of clay was a sealed coin of Postumus (c. 262) - the only stratified coin other than the coin of Gratian from the temple cella - which provides us a rough date for this metalled surface and the construction of the northeastern building. This dating is usually taken as the terminus post quem for the whole site assuming that the temple and the other buildings were built at the same time, especially in the light of the triangular layout Rodwell pointed out. Another metalled surface appeared over this clay layer and produced 54 coins, pottery, and small finds including a candle stick.⁶⁴ Embedded into the clay layer was an apsidal stone foundation open to the west side, and only a little over 1.5 metres at its widest. Around this structure rubble and roofing was found, and the metalling was stronger. Rahtz suggested that this may be the remains of a shrine or an altar⁶⁵ - which must have been contemporary with at least the first phase of the temple - this could explain the large number of coins in the area, second only to the temple itself (89 from the temple, 54 from this area) and many more than any other area. However he fails to provide any comparisons or further argument, and this structure plays no real role in any interpretations of the site. The coins from around the ’shrine’ are mainly late 3rd to mid 4th CE, there are later Valentinian (364 - 455) coins but these appear to be either further to the south and east or else above the roofing material, so may post-date the use of the ’shrine’ structure.⁶⁵

It is appealing to point out that at the same time this ’shrine’ went out of use the coins to the south of the temple entrance - interpreted as offerings - began to appear. Perhaps this represents a movement of the activities that used to take place at this ’shrine’ to this space outside the temple.

The Curse Tablets

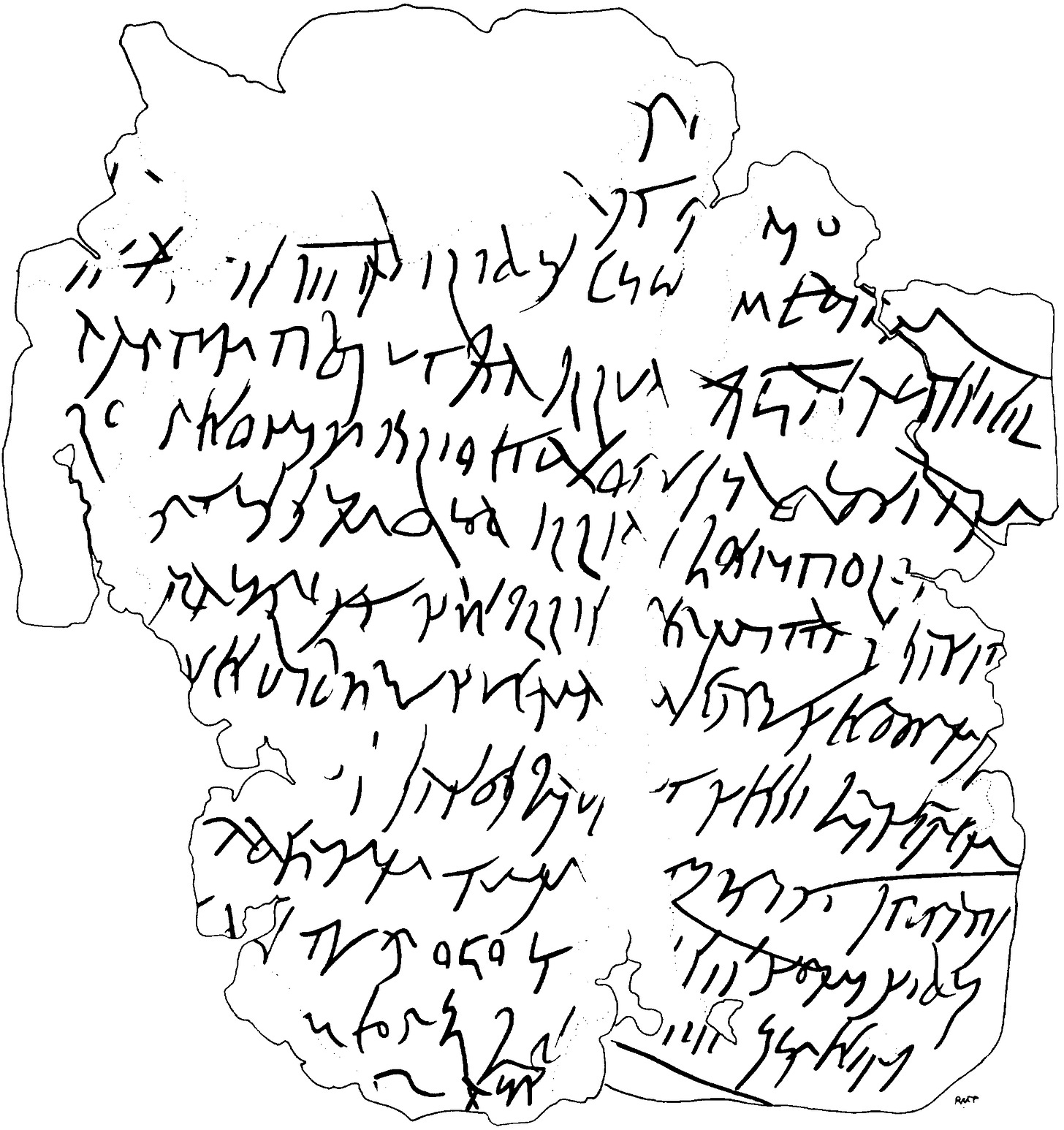

In 1984 Tomlin first published translations for three curse tablets found at Pagans Hill by metal detectorists the year prior.⁶⁶ Due to the unfortunate nature of their discovery we cannot say where on the site they came from, or anything about their archaeological context. As far as I am aware they are now lost to private ownership.

Of the three tablets - Brit 15.7, 15.8, and 15.9 - the first is the most complete and the last is too damaged to reconstruct any meaningful text. In the text of Brit 15.7, as reconstructed and translated by Tomlin, the author is petitioning a god to withhold from an individual named Vassicillus and his wife all manner of goods, such as health, eating, drinking, sleeping, and healthy children.⁶⁶ This is to continue to be the case until a sum of 3,000 denarii - which was stolen from the author’s home - is returned to the god’s temple. Upon completion, half of the sum would be granted to the god.

A few things stand out as interesting here, firstly, the author uses the term ‘your temple’ (ad fanum tuum).⁶⁷ If we can safely assume this is a reference to the Pagans Hill site where it was reportedly found, this provides direct evidence to confirm that the site is in fact a temple, rather than relying on comparing the form of the site to other sites. Secondly, the god is not being petitioned to inflict ill health, hunger, thirst, or insomnia. The god is instead being asked to withhold their positive counterparts. The difference might seem minor, but it is important to point out the implication that for the author the god is the source of these good things, with the negative counterparts merely being the side-effect caused by a withdrawal by the gods rather than the god directly inflicting woes themselves. Tomlin suggests that this tablet may have been dedicated to Mercury - a common enough dedication, but he recovers this from only two surviving letters and considers it himself to be conjecture.⁶⁸

Hill site where it was reportedly found, this provides direct evidence to confirm that the site is in fact a temple, rather than relying on comparing the form of the site to other sites. Secondly, the god is not being petitioned to inflict ill health, hunger, thirst, or insomnia. The god is instead being asked to withhold their positive counterparts. The difference might seem minor, but it is important to point out the implication that for the author the god is the source of these good things, with the negative counterparts merely being the side-effect caused by a withdrawal by the gods rather than the god directly inflicting woes themselves. Tomlin suggests that this tablet may have been dedicated to Mercury - a common enough dedication, but he recovers this from only two surviving letters and considers it himself to be conjecture.⁶⁸

Some other points about this tablet (15.7) have proved important for the dating of the temple. These are the hand used, and the amount of the denarii referenced. For Tomlin, this tablet was written in an Old-Roman cursive, which was going out of use by the middle of the 3rd CE. He states that he would not date it any later than first half of the 3rd CE and that it shows similarities to the hand used to write a wax tablet dated to the early 3rd CE found at the nearby Chew Valley Villa.⁶⁸

Tomlin also points out that the sum of 3,000 denarii would usually be remarkably high, but could be explained by the period of hyper-inflation the roman world entered in the first half of the 3rd CE.⁶⁸

Despite no identified archaeological evidence of a prior temple predating 262 CE, for Tomlin this tablet - directly referencing a temple - suggests the probable existence of one at this time.⁶⁸ Boon argues that it is easy enough to imagine that an older individual could have written the tablet using an out of fashion hand, given that they would have learnt the style earlier in the century before it went out of use.69 He also points out that the period of hyper-inflation lasted into the 300s CE, so we cannot use the amount of denarii alone to justify an earlier date.⁷⁰

Another option that neither discuss is that the probable round barrow - now underneath the temple - could have been the target for deposition of the tablet. As discussed, it is not uncommon for a temple to be located next to a barrow, and there are even other examples of temples being built on-top of them, such as Haddenham.¹⁷ Curse tablets inserted into graves are also not unknown, and are particularly well known from Gaul, such as the recent finds from Orleans.⁷¹ If we allow the same here we could imagine Brit 15.7 being deposited at the site of this round barrow before the temple was built, and explain why this site was chosen for a temple. Furthermore, as Tomlin points out,⁶⁸ Antonine period coins are reported to have been found at the site in the early 19th CE. Though we can’t know where exactly the coins came from we can be reasonably confident that there was activity at the site from the 2nd CE. There are problems with this however, the tablet refers to the fanum of a god, while the term doesn’t exclusively have to apply to a building I am unaware of any instances of it referring to a barrow or similar feature. Rahtz also reported nine inches of barren soil between the oval feature and the Roman layer, and as such it may be the case that the round barrow was destroyed long before the temple was built - though it would be a remarkable coincidence.¹³

The second tablet (Brit 15.8) was badly corroded and only two portions of text in rustic capitals can be read. We have ’eight times nine’, and ’let him be wearied by every sort of hardship’.⁶⁶ The first section Tomlin considers to be the use of some kind of ’magical’ number, as it is the product of 2³ and 3².⁷² The latter he considers to be a reference to Livy 40.22.15⁷² where we read:

“Philip, having wearied his troops with every sort of toil without having attained any result, and with his suspicions of his son increased because of the deceit of Didas, the general, returned to Macedonia”.⁷³

Aptly, earlier in the same passage we read:

“[...] they first laid waste the farm-houses far and wide, then even certain villages, not without great shame on the king’s part, when he heard the voices of his allies calling in vain upon the gods who protect alliances and upon his own name”.⁷³

Tablet 15.9 is unfortunately too damaged to recover any meaningful text, except that it appears to be a complaint - as expected.⁶⁶

Historical Context

Having introduced the site and examined its different features in detail we can now attempt to combine this information with the site’s unique historical context to try and draw out some general conclusions about the site and prior attempts to analyse it.

Given the temple’s construction around the year 262, we can place it in the earliest years of the ’Gallic Empire’. A brief break-away state that lasted fourteen years and was initially led by Postumus - a military commander who declared himself Emperor and held Gaul, Germania, Britannia, and Hispania - until its re-incorporation in the year 274.

Around 280 and 281 there appear to have been two rapid revolts. Both were quickly put down, but apparently dissatisfaction was great enough that only a few years later in 286 Carausius led a revolt taking northern Gaul with him and declaring himself emperor. This state would last ten years until Constantius re-took Britain through invasion in 296 from Carausius’ successor.

This is the context for the first phase of the temple, its construction, and period of decline before the later revival. I do not think we can say definitively why the temple had a period of decline, but the late 3rd CE for Britain appears even more tumultuous and chaotic than its time in the ’Gallic empire’ when the temple was constructed. It is hardly surprising that an elaborate temple would fail to be maintained at this time - perhaps funds were tight and needed elsewhere.

In the following years the empire would see drastic changes, Diocletian’s reforms would take place, Constantius would die while campaigning against the Picts, and his son Constantine I would be declared emperor in York in 306 and later become the first Christian emperor in 312 following his conversion. Following this Christianity would go from strength-to-strength while Polytheistic religion was legally diminished, until a brief revival in the mid 4th CE by the Emperor Julian.

It is during the time of Julian that we see the full revival of the temple and changes made to the layout of the cella. It would be tempting to connect this revival to Julian’s Polytheistic revival, and this may have played some role, perhaps encouraging investment in refurbishments especially if polytheistic philanthropy was seen as a beneficial to political clout. But there appears to have been no corresponding decline with the emergence of Christian political power from which to have a polytheistic revival. The decline at the end of the 3rd CE seems much more likely to be a result of the political and economic instability of that time, and then as soon as those factors stabilised the temple complex appears to have slowly begun to recover. The emerging Christian hegemony and legal restrictions on Polytheistic activity in the 4th CE do not appear to have prevented that - post-dating the decline of the temple by some decades.

Influences and integration

The temple with its octagonal form and its cella of piers or columns has been shown to draw on contemporary trends in religious architecture, visible not only at the nearby Nettleton Scrub but also on the continent, particularly Christian baptisteries from Rome, Aix, and Riez. This is an architectural trend that would continue through late antiquity reaching its zenith in the 6th CE with sites like the Basilica of San Vitale at Ravenna. So, we can say that whoever designed the Pagans Hill temple was well aware of trends from across the empire, drawing on these rather than adapting local building traditions such as the tried-and-true Romano-Celtic form.

We might have expected a temple being built during the emergence of a break- away state to follow native architectural traditions, or to become out of touch with trends due to isolation or the emergence of local identity, but this doesn’t seem to be the case. There is no sign of them rejecting ideas and practices perceived as ’foreign’ in favour of ’native’ alternatives, rather the opposite seems to have taken place.

If our earlier suggestion about the round barrow and the temple’s deliberate positioning over it is correct, we can suggest that the temple was constructed with a concern to integrate contemporary religious and architectural ideas within an ancient landscape that surely had its own meanings embedded within it. Perhaps with a growing interest in the ancient past they were seeking to render the past intelligible by incorporating it into contemporary religious practice - Romanising the past in a sense.

The people who designed and used this temple seem to have been well aware of religious trends across the empire, suggesting that they were well connected and had access to education. The curse tablets seem to bear this out with their literary references and ’magical numbers’. But at the same time they seem to have had one eye turned towards the past, and a particularly local past that must have had some religious meaning to them and could be readily incorporated into their contemporary practice.

Changing Ritual practices

A feature of the site during the Roman period which is often brought up is its cleanliness, this is often considered evidence for some special sense of ’purity’ at this site - this features prominently in discussions around the well as we have mentioned. This is true to a point, the courtyard area around the buildings was considered to be remarkably clean of finds, at temple sites we would expect this area to produce many stray finds such as coins, animal bones, or personal adornments. This does not appear to be the case here, and this could be interpreted as a focus on purity and cleanliness or strict control of the movement of pilgrims. But I would like to push back a bit and suggest that this temple was simply not very popular and was not frequented by large numbers of pilgrims. The site was not situated alongside a major roadway or embedded into a town or roadside settlement, the relatively small number of animal remains - which may have originated in a single event - suggests that feasting and sacrifice was rare and limited - increasingly true across the empire at this time.⁷⁴ We also know that in modern times the site has been robbed, both by workmen and metal detectorists, so there may be little - if there was ever much - left to be discovered of small finds.

Our understanding of how the pilgrims would have worshipped or made offerings at this early phase is quite limited. There is evidence for a relatively small amount of animal sacrifice, but this has not been associated with any particular phase of the temple. Coins that date from the mid to late 3rd CE were found in the temple and are likely to have been offerings, but only seven were found suggesting quite low levels of activity at the time, especially when we consider that these coins were un-stratified and could have been in circulation for a long time and only deposited later. Nonetheless even with slim evidence we can still expect worship to have gone on with all the standard motifs of Roman worship; including music, hymns, incense, and non-animal sacrifices - all of which are unlikely to have left any archaeological trace.

During this earliest phase coin depositions focused on the apsidal ’shrine’ structure and the well, but as we have seen from the start of the 4th CE depositions at the well - deliberate and accidental - ended, correspondingly coin deposits at the ‘shrine’ also ended at this time. It was during this same period that coins were increasingly being deposited at the temple building itself, specifically south of the entrance. Perhaps this represents a shifting of the practices taking place at the shrine and the well to the temple at this time, or the depositions at the temple may represent an entirely new set of rites that took the focus away from older ones. The relationships between these three features while they were all in use is difficult to express, but I think we can at least say that in the 4th CE rites became increasingly nucleated around the temple, perhaps justifying its renovation at this time.

This all adds up to be a significant reconfiguration of how the temple would have been experienced. Pilgrims or Temple staff couldn’t have stayed at the site for extended periods of time as the north-eastern building had gone out of use, the focus of coin offerings shifted from the external ’shrine’ or the well to a space outside the temple, the way religious iconography was displayed in the cella changed - being raised on a bench, and water was no longer gathered from the well. We can not say how exactly ritual and worship changed in this time, but surely we are looking at the tip of an iceberg, there must have been many more changes invisible to us, perhaps most importantly how people thought about and conceptualised their worship.

In summary, Pagans Hill is a site that teaches us much about the religious influences flowing into South-Eastern Britain during late antiquity, it shows us an interest in strongly structured and planned religious space, and how the people of the 3rd CE were interested in integrating new religious practices with an ancient past. It shows us that the instability at the end of that century could have a serious impact on the ways and places people worshipped, and how ritual in the following century was being reimagined and reinvented. Pagans Hill is a story of continued revival and re-interpretation of the past, and the lasting pull that past - imagined or not - has on religious thought.

References

I. D. Margary, in Roman Roads in Britain, Rev ed., 1967, pp. 139–40.

Rahtz and Watts, ‘Pagans Hill Revisited’, Archaeological Journal, vol. 146, pp. 337–338, 1989.

Rahtz and Watts, ‘Pagans Hill Revisited’, Archaeological Journal, vol. 146, pp. 337–338, 1989.

W. J. Wedlake, ‘The Excavation of the Shrine of Apollo at Nettleton, Wiltshire, 1956–1971’, Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, vol. 40, p. 197, 1982.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 124, 1951.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 125, 1951.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 20, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, pp. 27–8, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 29, 1958.

Rahtz and Watts, ‘Pagans Hill Revisited’, Archaeological Journal, vol. 146, p. 350, 1989.

Rahtz and Watts, ‘Pagans Hill Revisited’, Archaeological Journal, vol. 146, pp. 358–60, 1989.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 114 ff, 1951.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 122, 1951.

L. V. Grinsell, ‘Somerset Barrows Part 2: North and East’, Somerset Archaeology and Natural History, vol. 115, p. 98, 1971.

Apsimon, ‘The Roman temple on Brean Down, Somerset’, Proc University of Bristol Spelaeology Society, vol. 10, no. 3, 1965.

N. Wilson, ‘The Thornborough Romano-British Temple: a Reappraisal’, 2017.

C. Evans and I. Hodder, ‘Marshland Communities and cultural landscapes’, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2006.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 119-21, 1951.

Rahtz and Watts, ‘Pagans Hill Revisited’, Archaeological Journal, vol. 146, p. 335, 1989.

Lewis, in Temples in Roman Britain, 1966, p. 177.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 115, 1951.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 117, 1951.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 126, 1951.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, pp. 123–25, 1951.

W. Rodwell, ‘Temple Archaeology: problems of the present and portents for the future’, in Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, Parts i and ii: with a Gazetteer of Romano-Celtic Temples in Continental Europe, BAR Publishing, 1980, p. 211 ff. doi: 10.30861/9780860540854.

W. Rodwell, ‘Temple Archaeology: problems of the present and portents for the future’, in Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, Parts i and ii: with a Gazetteer of Romano-Celtic Temples in Continental Europe, BAR Publishing, 1980, p. 226. doi: 10.30861/9780860540854.

Lewis, in Temples in Roman Britain, 1966, p. 30.

W. Rodwell, ‘Temple Archaeology: problems of the present and portents for the future’, in Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, Parts i and ii: with a Gazetteer of Romano-Celtic Temples in Continental Europe, BAR Publishing, 1980, p. 240. doi: 10.30861/9780860540854.

W. Rodwell, ‘Temple Archaeology: problems of the present and portents for the future’, in Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, Parts i and ii: with a Gazetteer of Romano-Celtic Temples in Continental Europe, BAR Publishing, 1980, pp. 228–29. doi: 10.30861/9780860540854.

W. Rodwell, ‘Temple Archaeology: problems of the present and portents for the future’, in Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, Parts i and ii: with a Gazetteer of Romano-Celtic Temples in Continental Europe, BAR Publishing, 1980, p. 228. doi: 10.30861/9780860540854.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 116, 1951.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 121, 1951.

H. Koethe, in Die keltischen Rund- und Vielecktempel der Kaiserzeit, 1933, pp. 59–62.

P. Aupert, ‘Architecture gallo-romaine et tradition celtique: les puits et “grottes” du temple octogonal de Chassenon’, p. 147, 2005, doi: 10.3406/aquit.2005.870.

H. Koethe, in Die keltischen Rund- und Vielecktempel der Kaiserzeit, 1933, pp. 64–65, 66–68.

W. Rodwell, ‘Temple Archaeology: problems of the present and portents for the future’, in Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, Parts i and ii: with a Gazetteer of Romano-Celtic Temples in Continental Europe, BAR Publishing, 1980, p. 224. doi: 10.30861/9780860540854.

G. C. Boon, ‘A Roman Sculpture Rehabilitated: The Pagans Hill Dog’, Britannia, vol. 20, p. 207, 1989, doi: 10.2307/526163.

P. A. Rahtz, ‘The Roman Temple at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke, N Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 96, p. 128, 1951.

Rahtz and Watts, ‘Pagans Hill Revisited’, Archaeological Journal, vol. 146, p. 333, 1989.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 31, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 22, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Build- ings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 16, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, pp. 18–20, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 21, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, pp. 21–22, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, pp. 20–22, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Build- ings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 19, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, pp. 43–44, 1958.

G. C. Boon, ‘A Roman Sculpture Rehabilitated: The Pagans Hill Dog’, Britannia, vol. 20, pp. 201–217, 1989, doi: 10.2307/526163.

G. C. Boon, ‘A Roman Sculpture Rehabilitated: The Pagans Hill Dog’, Britannia, vol. 20, p. 205, 1989, doi: 10.2307/526163.

G. C. Boon, ‘A Roman Sculpture Rehabilitated: The Pagans Hill Dog’, Britannia, vol. 20, p. 216, 1989, doi: 10.2307/526163.

Rahtz and Watts, ‘Pagans Hill Revisited’, Archaeological Journal, vol. 146, pp. 341–45, 1989.

Rahtz and Watts, ‘Pagans Hill Revisited’, Archaeological Journal, vol. 146, p. 358, 1989.

Rahtz and Watts, ‘Pagans Hill Revisited’, Archaeological Journal, vol. 146, p. 359, 1989.

A. King and K. Reily, ‘Animal Remains from Temples in Roman Britain’, Britannia, vol. 36, p. 330, 2005.

Woodward and Leach, in The Uley Shrines: Excavation of a Ritual Complex on West Hill, Uley, Gloucestershire, 1993, p. 299.

A. King and K. Reily, ‘Animal Remains from Temples in Roman Britain’, Britannia, vol. 36, pp. 331–32, 2005.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, pp. 24–25, 1958.

A. M. Ap Simon, P. A. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Iron Age A Ditch and Pottery at Pagan’s Hill, Chew Stoke’, Proceedings of the University of Bristol Spelæological Society, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 98–99, 1957.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 25, 1958.

Rahtz and Watts, ‘Pagans Hill Revisited’, Archaeological Journal, vol. 146, p. 356, 1989.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, pp. 28–29, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Build- ings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 27, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 26, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, pp. 37–38, 1958.

P. A. Rahtz, M. H. Rahtz, and L. G. Harris, ‘The Temple Well and Other Buildings at Pagans Hill, Chew Stoke, North Somerset’, Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, vol. 101–102, p. 30, 1958.

S. S. Frere, M. W. C. Hassall, and R. S. O. Tomlin, ‘Roman Britain in 1983’, Britannia, vol. 15, p. 336, 1984, doi: 10.2307/526612.

S. S. Frere, M. W. C. Hassall, and R. S. O. Tomlin, ‘Roman Britain in 1983’, Britannia, vol. 15, p. 339, 1984, doi: 10.2307/526612.

S. S. Frere, M. W. C. Hassall, and R. S. O. Tomlin, ‘Roman Britain in 1983’, Britannia, vol. 15, p. 351, 1984, doi: 10.2307/526612.

G. C. Boon, ‘A Roman Sculpture Rehabilitated: The Pagans Hill Dog’, Britannia, vol. 20, p. 210, 1989, doi: 10.2307/526163.

G. C. Boon, ‘A Roman Sculpture Rehabilitated: The Pagans Hill Dog’, Britannia, vol. 20, p. 211, 1989, doi: 10.2307/526163.

‘Tablette de défixion’, Service Archeologie Oreleans. Accessed: May 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://archeologie.orleans-metropole.fr/musee-virtuel

S. S. Frere, M. W. C. Hassall, and R. S. O. Tomlin, ‘Roman Britain in 1983’, Britannia, vol. 15, p. 352, 1984, doi: 10.2307/526612.

Livy. Books XL-XLII With An English Translation. Cambridge. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1938.

J. N. Bremmer, ‘Transformations and Decline of Sacrifice in Imperial Rome and Late Antiquity’, in Transformationen paganer Religion in der römischen Kaiserzeit: Rahmenbedingungen und Konzepte, M. Blömer and B. Eckhardt, Eds., De Gruyter, 2018, pp. 215–256.